"One woman.

One great mystery.

One consuming obsession.

40,000 restaurants."

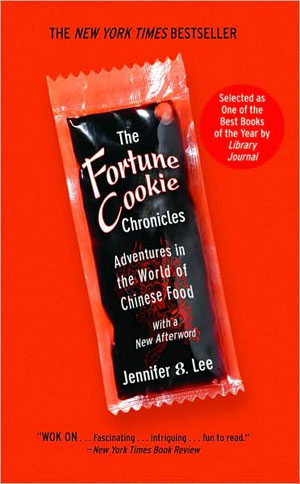

Remember at the beginning of the summer when I bought all those books I said I'd review? Yeah, I forgot. Well the most memorable of the lot was The Fortune Cookie Chronicles.

Remember at the beginning of the summer when I bought all those books I said I'd review? Yeah, I forgot. Well the most memorable of the lot was The Fortune Cookie Chronicles.Jennifer 8 Lee is a New York Times reporter who started her professional investigation into Chinese food in a strange place-the Lottery. She starts the book with a very strange foray into the state by state lottery system and gets to the point by exploring how one day in 2005, 110 people managed to choose 5 out of 6 numbers correctly in a Powerball drawing. At first the lottery officials thought this was some kind of fraud, but the real reason behind so many choosing the same numbers? Fortune cookies! All over the country, Americans love of Chinese food led them to have faith in the numbers printed below their fortunes. So Lee investigated the invention of the fortune cookie, the various people and restaurants that led the lottery winners down their lucky path, and the dishes that Americans hold so dear.

Lee remarks that "our benchmark for Americanness is apple pie. But ask yourself: how often do you eat apple pie? How often do you eat Chinese food?" An interesting point. I think we have Chinese food in my house more often than any other kind (other than Mexican food). I have always loved it and M. has as well. I remember my mom being surprised one day that I had it two days in a row. One restaurant on Friday and a different one on Saturday with friends. I didn't even think of it as odd. I mean, Chinese people eat it every day, right? But this version of Chinese food that we eat is not very similar to the "authentic" cuisine of contemporary Chinese immigrants. Nonetheless, it's part of the American experience.

Lee's look at the food we call home takes many turns. She explores the cultural history of the Chinese in the United States, with good background research on the reasons for booms in Chinese immigration in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. She records early fears of Chinese food documented primarily the West, complete with a Mark Twain anecdote about fears of mice in the egg rolls.

She traces how the Japanese internment during World War II created the boom in Chinese food as a regular and inexpensive alternative to Anglo-American cuisine, as well as the popularity of the fortune cookie at the end of the meal.

She explores Misa Chang's entrepreneurial invention of Chinese food delivery inlate 1970s New York, and the resulting tidal wave of paper menus and Chinese-American delivery men across New York City.

The most intriguing section of the book is devoted to the average restaurant worker's dangerous and expensive journey from China to the United States.

I was actually reminded of this book yesterday when I went to a Mongolian BBQ restaurant that I have been going to for about 13 years. Introduced to it by friends in college, it has since been a staple. Now, Mongolian BBQs might be a whole different thing, but this particular restaurant was run by Chinese first-generation immigrants. I noticed that the restaurant had changed hands, because the owner and her employees (who were there no matter when I showed up) were missing. My companion told me they hadn't been there in a while, and yet the place looked exactly the same. The menu was the same. The quality of the food was the same. So very odd. Unless you understand how the restaurant business, and in particular the Chinese food business works.

A large portion of Chinese restaurant workers come from one province in China, Fujian, where its inhabitants will pay exorbitant amounts (we're talking tens of thousands of dollars) to get young men and sometimes women from the shores of China into the United States.

According to Lee, many restaurant workers lead a rather nomadic life, moving across the country to work. There are Chinese restaurants everywhere, and when one owner decides to move on for whatever reason, another comes to take over, sometimes changing nothing other than the staff. Though there are Chinese restaurants everywhere, not every town has a Chinese immigrant enclave, so job seekers usually find out about the available job via employment agencies specializing in Chinese restaurant workers. They provide them with the info on the monthly salary and the bus that will take them there. Lee's investigation is fascinating and even though she explores the vast network of people and money that go into staffing the restaurants, she still connects the reader to the individual experience by focusing on two or three stories of families, single men, and young people in the business. The one true day of peace and rest for the Chinese restaurant worker? Thanksgiving.

In addition to traveling the world looking for the "best" Chinese restaurant, she looks at the individual dishes and ingredients too. A visit to General Tso's birthplace is hilarious. No they don't really eat chicken there. The creation of Chop Suey is another fun story. As are the various fueds and wars over soy sauce, takeout containers, and fortune cookies.

She looks at who writes those fortunes and how they come up with them. Apparently, there's some trial and error. For instance, "You will soon meet a handsome man" caused a few older Southern women to complain (I'm guessing straight men who received these took them to the grave). "Women marry because they don't want to work" actually brought complaint from a young woman in the 1950s. I've been bummed on a fortune cookie, but I can't say I've ever been so perturbed that I've felt the need to call up the company and make a fuss. But I guess they've been working on not angering customers for a while!

I've given you tons of info on the book's contents and it still just touches the surface. Probably the best examination of American foodways I've read in a while, this is one you should read. Just don't blame me if you end up changing your dinner plans after reading it.

No comments:

Post a Comment